Netflix

Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

| Type of business | Public |

|---|---|

Type of site | OTT platform PPV |

| Traded as |

|

| Founded | August 29, 1997[1] in Scotts Valley, California |

| Headquarters | Los Gatos, California, U.S.

Production hubs:

|

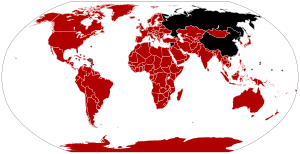

| Area served | Worldwide (excluding mainland China, Syria, North Korea and Crimea)[7] |

| Founder(s) | |

| Key people |

|

| Industry | Tech & Entertainment, mass media |

| Products |

|

| Services |

|

| Revenue | |

| Operating income | |

| Net income | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Employees | 12,135 (2021) |

| Divisions | US Streaming International Streaming Domestic DVD |

| Subsidiaries |

|

| URL | netflix.com |

| Registration | Required |

| Users | |

| [13] | |

Netflix, Inc. is an American over-the-top content platform and production company headquartered in Los Gatos, California. Netflix was founded in 1997 by Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph in Scotts Valley, California. The company's primary business is a subscription-based streaming service offering online streaming from a library of films and television series, including those produced in-house.[14] In January 2021, Netflix reached 203.7 million subscribers, including 73 million in the United States.[15][16] It is available worldwide except in the following: mainland China (due to local restrictions), Syria, North Korea, and Crimea (due to US sanctions). It was reported in 2020 that Netflix's operating income is $1.2 billion.[17] The company has offices in France, Brazil, the Netherlands, India, Japan, South Korea, and the United Kingdom.[18] Netflix is a member of the Motion Picture Association (MPA), producing and distributing content from countries all over the globe.

Netflix's initial business model included DVD sales and rental by mail, but Hastings abandoned the sales about a year after the company's founding to focus on the initial DVD rental business.[14][19] Netflix expanded its business in 2007 with the introduction of streaming media while retaining the DVD and Blu-ray rental business. The company expanded internationally in 2010 with streaming available in Canada,[20] followed by Latin America and the Caribbean. Netflix entered the content-production industry in 2013, debuting its first series House of Cards.

Since 2012, Netflix has taken more of an active role as producer and distributor for both film and television series, and to that end, offers a variety of "Netflix Original" content through its online library.[21] By January 2016, Netflix services operated in more than 190 countries.[22] Netflix released an estimated 126 original series and films in 2016, more than any other network or cable channel.[23] Their efforts to produce new content, secure the rights for additional content, and diversify through 190 countries have resulted in the company racking up billions in debt: $21.9 billion as of September 2017, up from $16.8 billion from the previous year.[24] $6.5 billion of this is long-term debt, with the remainder in long-term obligations.[25] In October 2018, Netflix announced it would raise another $2 billion in debt to help fund new content.[26] On July 10, 2020, Netflix became the largest entertainment/media company by market capitalization.[27]

History

Establishment

Marc Randolph[30][31] and Reed Hastings founded Netflix on August 29, 1997 in Scotts Valley, California. Randolph worked as a marketing director for Hastings's company, Pure Atria.[32] Randolph had co-founded MicroWarehouse, a computer mail-order company; Borland International later employed him as vice president of marketing. Hastings, a computer scientist and mathematician, sold Pure Atria to Rational Software Corporation in 1997 for $700 million in what was then the biggest acquisition in Silicon Valley history. The two came up with the idea for Netflix when commuting between their homes in Santa Cruz and Pure Atria's headquarters in Sunnyvale while waiting for government regulators to approve the merger,[33] although Hastings has given several different explanations for how the idea came about.[34]

Hastings invested $2.5 million in startup cash for Netflix.[35][19] Randolph admired the fledgling e-commerce company Amazon and wanted to find a large category of portable items to sell over the Internet using a similar model. Hastings and Randolph considered and rejected VHS tapes as too expensive to stock and too delicate to ship. When they heard about DVDs, first introduced in the United States on March 24, 1997,[36] they tested the concept of selling or renting DVDs by mail by mailing a compact disc to Hastings's house in Santa Cruz. When the disc arrived intact, they decided to take on the $16 billion home-video sales and rental industry.[33] Hastings is often quoted saying that he decided to start Netflix after being fined $40 at a Blockbuster store for being late to return a copy of Apollo 13, but he and Randolph designed this apocryphal story to explain the company's business model and motivation.[33]

Netflix launched as the world's first online DVD-rental store, with only 30 employees and 925 titles available—almost the entire catalogue of DVDs at the time[37]—using the pay-per-rent model, with rates and due dates similar to those of its brick-and-mortar competitor, Blockbuster.[38][33]

Membership fee, Blockbuster acquisition offer, growth start

Netflix introduced the monthly subscription concept in September 1999,[39] and then dropped the single-rental model in early 2000. Since that time (see Technical details of Netflix), the company has built its reputation on the business model of flat-fee unlimited rentals without due dates, late fees, shipping and handling fees, or per-title rental fees.[40]

In 2000, when Netflix had just about 300,000 subscribers and relied on the US Postal Service for the delivery of their DVDs, their losses would total $57 million and offered to be acquired by Blockbuster for $50 million. They proposed that Netflix, which would be renamed as Blockbuster.com, would handle the online business, while Blockbuster would take care of the DVDs, making them less dependent on the US Postal Service. The offer was declined.[41][42][43][44]

While they experienced fast growth in early 2001, both the dot-com bubble burst and the September 11 attacks occurred later that year, affecting the company badly and forcing them to lay off one-third of their 120 employees. However, sales of DVD players finally took off as they became more affordable, selling for about $200 around Thanksgiving time, becoming one of that year's most popular Christmas gifts. By early 2002, Netflix saw a huge increase in their subscription business.[45][46]

Netflix initiated an initial public offering (IPO) on May 29, 2002, selling 5.5 million shares of common stock at the price of US$15.00 per share. On June 14, 2002, the company sold an additional 825,000 shares of common stock at the same price. After incurring substantial losses during its first few years, Netflix posted its first profit during the fiscal year 2003, earning US$6.5 million profit on revenues of US$272 million. In 2005, 35,000 different films were available, and Netflix shipped 1 million DVDs out every day.[47]

Randolph, a dominant producer and board member for Netflix, retired from the company in 2004.[48]

Netflix was sued in 2004 for false advertising in relation to claims of "unlimited rentals" with "one-day delivery".[49]

Entertainment dominance, presence, and continued growth

Netflix has been one of the most successful dot-com ventures. In September 2002, The New York Times reported that, at the time, Netflix mailed about 190,000 discs per day to its 670,000 monthly subscribers.[50] The company's published subscriber count increased from one million in the fourth quarter of 2002 to around 5.6 million at the end of the third quarter of 2006, to 14 million in March 2010. Netflix's early growth was fueled by the fast spread of DVD players in households; in 2004, nearly two-thirds of United States homes had a DVD player. Netflix capitalized on the success of the DVD and its rapid expansion into United States homes, integrating the potential of the Internet and e-commerce to provide services and catalogs that bricks-and-mortar retailers could not compete with. Netflix also operates an online affiliate program which has helped to build online sales for DVD rentals as well. The company offers unlimited vacation time for salaried workers and allows employees to take any amount of their paychecks in stock options.[51]

By 2010, Netflix's streaming business had grown so quickly that within months the company had shifted from the fastest-growing customer of the United States Postal Service's first-class service to the largest source of Internet streaming traffic in North America in the evening. In November, it began offering a standalone streaming service separate from DVD rentals.[52]

On September 18, 2011, Netflix announced its intentions to rebrand and restructure its DVD home media rental service as an independent subsidiary called Qwikster, separating DVD rental and streaming services.[53][54][55] Andy Rendich, a 12-year Netflix veteran, was to be CEO of Qwikster. Qwikster would carry video games whereas Netflix did not.[56] However, in October 2011, Netflix announced that it would retain its DVD service under the name Netflix and would not, in fact, create Qwikster for that purpose.[57]

In April 2011, Netflix had over 23 million subscribers in the United States and over 26 million worldwide.[58] In July 2011, Netflix changed its prices, charging customers for its mail rental service and streaming service separately. This meant a price increase for customers who wanted to continue receiving both services.[59] On October 24, Netflix announced 800,000 unsubscribers in the United States during the third quarter of 2011, and more losses were expected in the fourth quarter of 2011. However Netflix's income jumped 63% for the third quarter of 2011.[60][61] Year-long, the total digital revenue for Netflix reached at least $1.5 billion.[62] On January 26, 2012, Netflix added 610,000 subscribers in the United States by the end of the fourth quarter of 2011, totaling 24.4 million United States subscribers for this time period.[63] On October 23, however, Netflix announced an 88% decline in profits for the third quarter of the year.[64]

In April 2012, Netflix filed with the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to form a political action committee (PAC) called FLIXPAC.[65] Politico referred to the PAC, based in Los Gatos, California, as "another political tool with which to aggressively press a pro-intellectual property, anti-video-piracy agenda".[65] The hacktivist group Anonymous called for a boycott of Netflix following the news.[66] Netflix spokesperson Joris Evers indicated that the PAC was not set up to support the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and the PROTECT IP Act (PIPA), tweeting that the intent was to "engage on issues like net neutrality, bandwidth caps, UBB and VPPA".[67][68]

In February 2013, Netflix announced it would be hosting its own awards ceremony, The Flixies.[69] On March 13, 2013, Netflix announced a Facebook implementation, letting United States subscribers access "Watched by your friends" and "Friends' Favorites" by agreeing.[70] This was not legal until the Video Privacy Protection Act of 1988 was modified in early 2013.[71]

Video on demand introduction, declining DVD sales, global expansion

For some time, the company had considered offering movies online, but it was only in the mid-2000s that data speeds and bandwidth costs had improved sufficiently to allow customers to download movies from the net. The original idea was a "Netflix box" that could download movies overnight, and be ready to watch the next day. By 2005, they had acquired movie rights and designed the box and service, and were ready to go public with it. But after discovering YouTube, and witnessing how popular streaming services were despite the lack of high-definition content, the concept of using a hardware device was scrapped and replaced with a streaming concept instead, a project that was completed in 2007.[72]

Netflix developed and maintains an extensive personalized video-recommendation system based on ratings and reviews by its customers. On October 1, 2006, Netflix offered a $1,000,000 prize to the first developer of a video-recommendation algorithm that could beat its existing algorithm Cinematch, at predicting customer ratings by more than 10%.[73]

In February 2007, the company delivered its billionth DVD,[74] and began to move away from its original core business model of DVDs, by introducing video on demand via the Internet. Netflix grew as DVD sales fell from 2006 to 2011.[75][76]

Another contributing factor for the company's online DVD rental success was that they could offer a much larger selection of movie titles to choose from than Blockbuster's rental outlets. But when they started to offer streaming content for free to its subscribers in 2007, it could offer no more than about 1000 movies and TV-shows, just 1% compared to its more than 100,000 different DVD titles. Yet as the popularity kept growing, the number of titles available for streaming was increasing as well and had reached 12,000 movies and shows in June 2009. One of the key things about Netflix was that it had a recommendation system known as Cinematch, which not only got viewers to remain attached to the service, by creating a switching cost, but it also brought out those movies which were underrated so that customers could view those movies too from their recommendations. This was an attribute that not only benefited Netflix but also benefited its viewers and those studios which were minor compared to others.[77]

In January 2013, Netflix reported that it had added two million United States customers during the fourth quarter of 2012, with a total of 27.1 million United States streaming customers, and 29.4 million total streaming customers. In addition, revenue was up 8% to $945 million for the same period.[78][79] That number increased to 36.3 million subscribers (29.2 million in the United States) in April 2013.[80] As of September 2013, for that year's third quarter report, Netflix reported its total of global streaming subscribers at 40.4 million (31.2 million in the United States).[81] By the fourth quarter of 2013, Netflix reported 33.1 million United States subscribers.[82] By September 2014, Netflix had subscribers in over 40 countries, with intentions of expanding their services in unreached countries.[83] By October 2018, Netflix's customer base reached 137 million worldwide, confirming its rank as by far the world's biggest online subscription video service.[84]

Early Netflix Original content

Netflix has played a prominent role in independent film distribution. Through its division Red Envelope Entertainment, Netflix licensed and distributed independent films such as Born into Brothels and Sherrybaby. As of late 2006, Red Envelope Entertainment also expanded into producing original content with filmmakers such as John Waters.[85] Netflix closed Red Envelope Entertainment in 2008, in part to avoid competition with its studio partners.[86][87]

Rebranding and wider international expansion

In April 2014, Netflix approached 50 million global subscribers with a 32.3% video streaming market share in the United States. Netflix operated in 41 countries around the world.[88] In June 2014, Netflix unveiled a global rebranding: a new logo, which uses a modern typeface with the drop shadowing removed, and a new website UI. The change was controversial; some liked the new minimalist design, whereas others felt more comfortable with the old interface.[89] In July 2014, Netflix surpassed 50 million global subscribers, with 36 million of them being in the United States.[90]

Following the launch of Daredevil in April 2015, Netflix director of content operations Tracy Wright announced that Netflix had added support for audio description (a narration track that contains aural descriptions of key visual elements for the blind or visually impaired), and had begun to work with its partners to add descriptions to its other original series over time.[91][92] The following year, as part of a settlement with the American Council of the Blind, Netflix agreed to provide descriptions for its original series within 30 days of their premiere, and add screen reader support and the ability to browse content by availability of descriptions.[93]

At the 2016 Consumer Electronics Show, Netflix announced a major international expansion of its service into 150 additional countries. Netflix promoted that with this expansion, it would now operate in nearly all countries that the company may legally or logistically operate in. A notable exception was China, citing the barriers of operating Internet and media services in the country due to its regulatory climate. Reed Hastings stated that the company was planning to build relationships with local media companies that could serve as partners for distributing its content in the country (with a goal to concentrate primarily on its original content), but stated that they were in no hurry, and could thus take "many years".[94][95][96][97][98][99][100]

Also in January 2016, Netflix announced it would begin blocking virtual private networks (VPNs) since they can be used to watch videos from a country where they are unavailable.[101] The result of the VPN block is that people can only watch videos available worldwide and other videos are hidden from search results, which can however be found on the Unofficial Netflix Online Global Search (uNoGS) website.[102] At the same time, Netflix reported 74.8 million subscribers and predicted it would add 6.1 million more by March 2016. Subscription growth has been fueled by its global expansion.[103] By the end of the year, Netflix added a feature to allow customers to download and play select movies and shows while offline.[104]

In February 2017, Netflix signed a music publishing deal with BMG Rights Management, where BMG will oversee rights outside of the United States for music associated with Netflix original content. Netflix continues to handle these tasks in-house in the United States.[105] On April 17, 2017, it was reported that Netflix was nearing 100 million subscribers.[106] On April 25, 2017, Netflix announced that it had reached a licensing deal in China with the Baidu-owned streaming service iQiyi, to allow selected Netflix original content to be distributed in China on the platform.[95] The Los Angeles Times stated: "Its series and movies account for more than a third of all prime-time download Internet traffic in North America."[107]

On January 22, 2018, the company crossed $100 billion in market capitalization, becoming the largest digital media and entertainment company in the world, bigger than every traditional media company except for AT&T, Comcast and Disney[108][109] and the 59th largest publicly traded company in the US S&P 500 Index.[110]

On March 2, 2018, Netflix stock price surged to a new all-time high of $301.05 beating its 12-month price target of $300.00, and finishing the session with a market capitalization of $130 billion putting it within shouting distance of traditional media giants like Disney ($155 billion) and Comcast ($169 billion). The milestone came a day after British satcaster Sky announced a new agreement with Netflix to integrate Netflix's subscription VOD offering into its pay-TV service. Customers with its high-end Sky Q set-top box and service will be able to see Netflix titles alongside their regular Sky channels.[111]

In July 2018, it was announced that Netflix had inked a deal with top Hollywood awards strategist Lisa Taback to acquire her independent LT-LA consulting firm and move her in-house at the streaming giant. The deal gives her the title VP Talent Relations, and she will lead the company's talent relations and awards teams. It also means she will provide her services exclusively to Netflix.[10]

According to Global Internet Phenomena Report Netflix consumes 15% of all Internet bandwidth globally, the most by any single application.[112]

In October 2018, Netflix acquired ABQ Studios, a film and TV production facility with eight sound stages in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The reported purchase price is under $30 million.[113]

Netflix sought and was approved for membership into the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) on January 22, 2019, as the first streaming service to become a member of the association.[114]

In April 2019, it was announced that Netflix was seeking to purchase Grauman's Egyptian Theatre from the American Cinematheque to use as a special events venue,[115] Later on May 29, 2020, it was announced that Netflix will acquire the theater and invests in some renovations of it.[116]

In July 2019, Netflix announced that it would be opening a hub at Shepperton Studios as part of a deal with Pinewood Group.[117]

During the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 when many cinemas around the world were closed, Netflix acquired 16 million new subscribers, which almost doubles the result of the final months of 2019.[118]

On July 30, 2020, it was revealed that Netflix has invested in Black Mirror creators Charlie Brooker and Annabel Jones’ new production outfit Broke And Bones in a first-of-its-kind deal for the streamer in the UK, which could ultimately see it take full control of the company for around $100M.[12] Most recently, Netflix announced a restructuring in entertainment.[119] In September 2020, Hastings released a book on Netflix titled No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention, which was co-authored by Erin Meyer.[120] By October 2020, Netflix had over 195 million paid subscriptions worldwide, including 73 million in the United States.[121]

Ownership

As of 2017, Netflix shares were mainly held by institutional investors, including Capital Research Global Investors, The Vanguard Group, BlackRock and others.[122]

Corporate culture

Netflix grants all employees extremely broad discretion with respect to business decisions, expenses, and vacation—but in return expects consistently high performance, as enforced by what is known as the "keeper test."[123][124] All supervisors are expected to constantly ask themselves if they would fight to keep an employee. If the answer is no, then it is time to let that employee go.[125] A slide from an internal presentation on Netflix's corporate culture summed up the test as: "Adequate performance gets a generous severance package."[124] Such packages reportedly range from four months' salary in the United States to as much as six months in the Netherlands.[125]

About the culture that results from applying such a demanding test, Hastings has said that "You gotta earn your job every year at Netflix,"[126] and, "There's no question it's a tough place...There's no question it's not for everyone."[127] Hastings has drawn an analogy to athletics: professional athletes lack long-term job security because an injury could end their career in any particular game, but they learn to put aside their fear of that constant risk and focus on working with great colleagues in the current moment.[128]

Finance

For the fiscal year 2018, Netflix reported earnings of US$1.21 billion, with an annual revenue of US$15.8 billion, an increase of approximately 116% over the previous fiscal cycle. Netflix's shares traded at over $400 per share at its highest price in 2018, and its market capitalization reached a value of over US$180 billion in June 2018. Netflix ranked 261 on the 2018 Fortune 500 list of the largest United States companies by revenue.[129] Netflix was the top-performing S&P 500 stock of the 2010s, with a total return of 3,693%.[130][131]

| Year | Revenue in mil. USD-$ |

Net income in mil. USD-$ |

Price per Share in USD-$ |

Employees | Paid memberships in mil. |

Fortune 500 rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 682 | 42 | 2.59 | 2.5 | ||

| 2006 | 997 | 49 | 3.69 | 4.0 | ||

| 2007 | 1,205 | 67 | 3.12 | 7.3 | ||

| 2008 | 1,365 | 83 | 4.09 | 9.4 | ||

| 2009 | 1,670 | 116 | 6.32 | 11.9 | ||

| 2010 | 2,163 | 161 | 16.82 | 2,180 | 18.3 | |

| 2011 | 3,205 | 226 | 27.49 | 2,348 | 21.6 | |

| 2012 | 3,609 | 17 | 11.86 | 2,045 | 30.4 | |

| 2013 | 4,375 | 112 | 35.27 | 2,022 | 41.4 | |

| 2014 | 5,505 | 267 | 57.49 | 2,450 | 54.5 | |

| 2015 | 6,780 | 123 | 91.90 | 3,700 | 70.8 | #474 |

| 2016 | 8,831 | 187 | 102.03 | 4,700 | 89.1 | #379 |

| 2017 | 11,693 | 559 | 165.37 | 5,500 | 117.5 | #314 |

| 2018 | 15,794 | 1,211 | 7,100 | 139.3 | #261 | |

| 2019 | 20,156 | 1,867 | 8,600 | 167.1 | #197 | |

| 2020 | 24,996 | 2,761 | 9,400 | 203.7 | #164 |

Services

Netflix's video on demand streaming service, formerly branded as Watch Now, allows subscribers to stream television series and films via the Netflix website on personal computers, or the Netflix software on a variety of supported platforms, including smartphones and tablets, digital media players, video game consoles and smart TVs.[132] According to a Nielsen survey in July 2011, 42% of Netflix users used a standalone computer, 25% used the Wii, 14% by connecting computers to a television, 13% with a PlayStation 3 and 12% an Xbox 360.[133]

When the streaming service was first launched, Netflix's disc rental subscribers were given access at no additional charge. Subscribers were allowed approximately one hour of streaming per dollar spent on the monthly subscription (a $16.99 plan, for example, entitled the subscriber to 17 hours of streaming media). In January 2008, however, Netflix lifted this restriction, at which point virtually all rental-disc subscribers became entitled to unlimited streaming at no additional cost (however, subscribers on the restricted plan of two DVDs per month ($4.99) remained limited to two hours of streaming per month). This change came in a response to the introduction of Hulu and to Apple's new video-rental services.[134] Netflix later split DVD rental subscriptions and streaming subscriptions into separate, standalone services, at which point the monthly caps on Internet streaming were lifted.[135]

Netflix service plans are currently divided into three price tiers; the lowest offers standard definition streaming on a single device (and up to 480p quality),[136][137] the second allows high definition streaming on two devices simultaneously (and up to 1080p quality), and the "Platinum" tier allows simultaneous streaming on up to four devices (and up to 4K quality on supported devices and internet connections). The HD subscription plan historically cost US$7.99; in April 2014, Netflix announced that it would raise the price of this plan to $9.99 for new subscribers, but that existing customers would be grandfathered under this older price until May 2016, after which they could downgrade to the SD-only tier at the same price, or pay the higher fee for continued high definition access.[138][139][140]

In July 2016, a Netflix subscriber sued the company over the price increases, alleging he was told by a Netflix customer support representative in 2011 that they would pay the same price in perpetuity as long as they maintained their subscription continuously.[141]

On November 30, 2016, Netflix launched an offline playback feature, allowing users of the Netflix mobile apps on Android or iOS to cache content on their devices in standard or high quality for viewing without an Internet connection. The feature was initially available on selected series and films but Netflix stated that more content would be supported by the feature over time.[142][143][144] Netflix will partner with airlines to provide them with its mobile streaming technology. This will start in early 2018 as part of an effort to get airlines to provide better in-flight Wi-Fi.[145]

In 2018, Netflix introduced the "Skip Intro" feature which allows customers to skip the intros to shows on its platform. They do so through a variety of techniques including manual reviewing, audio tagging, and machine learning.[146]

In March 2021, Netflix started warning users for sharing passwords of their account to others.[147]

History

On October 1, 2008, Netflix announced a partnership with Starz to bring 2,500+ new films and shows to "Watch Instantly", under Starz Play.[148]

In August 2010, Netflix reached a five-year deal worth nearly $1 billion to stream films from Paramount, Lionsgate and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The deal increased Netflix's annual spending fees, adding roughly $200 million per year. It spent $117 million in the first six months of 2010 on streaming, up from $31 million in 2009.[149]

On July 12, 2011, Netflix announced that it would separate its existing subscription plans into two separate plans: one covering the streaming and the other DVD rental services.[150] The cost for streaming would be $7.99 per month, while DVD rental would start at the same price. The announcement led to panned reception among Netflix's Facebook followers, who posted negative comments on its wall.[151] Twitter comments spiked a negative "Dear Netflix" trend.[151] The company defended its decision during its initial announcement of the change:

"Given the long life we think DVDs by mail will have, treating DVDs as a $2 add-on to our unlimited streaming plan neither makes great financial sense nor satisfies people who just want DVDs. Creating an unlimited-DVDs-by-mail plan (no streaming) at our lowest price ever, $7.99, does make sense and will ensure a long life for our DVDs-by-mail offering."[150]

In a reversal, Netflix announced in October that its streaming and DVD-rental plans would remain branded together.[152]

In January 2018, Netflix named Spencer Neumann as the new CFO.[citation needed]

In January 2020, Netflix opened a new office in Paris with 40 employees.[citation needed]

In July 2020, Netflix appointed Ted Sarandos as co-CEO.[153]

Disc rental

In the United States, the company provides a monthly flat-fee for DVD and Blu-ray rentals. A subscriber creates a rental queue, a list, of films to rent. The films are delivered individually via the United States Postal Service from regional warehouses. As of March 28, 2011, Netflix had 58 shipping locations throughout the United States.[154] The subscriber can keep the rented disc as long as desired, but there is a limit on the number of discs that each subscriber can have simultaneously via different tiers. To rent a new disc, the subscriber must return the previous disc in a metered reply mail envelope. Upon receipt, Netflix ships the next available disc in the subscriber's rental queue.

Netflix offers pricing tiers for DVD rental. On November 21, 2008, Netflix began offering subscribers rentals on Blu-ray for an additional fee. Also, Netflix sold used discs, delivered, and billed identically as rentals. This service was discontinued at the end of November.[155]

On January 6, 2010, Netflix agreed with Warner Bros. to delay new release rentals 28 days prior to retail, in an attempt to help studios sell physical copies, and similar deals involving Universal and 20th Century Fox were reached on April 9.[156][157][158] In 2011, Netflix split its service pricing. Currently, Netflix's disc rental memberships range from $7.99 to $19.99/m, including a free one-month trial and unlimited DVD exchanges.

On September 18, 2011, Netflix announced that it would split out and rebrand its DVD-by-mail service as Qwikster. CEO Reed Hastings justified the decision, stating that "we realized that streaming and DVD by mail are becoming two quite different businesses, with very different cost structures, different benefits that need to be marketed differently, and we need to let each grow and operate independently." It was also announced that the re-branded service would add video game rentals. The decision to split the services was widely criticized; it was noted that the two websites would have been autonomous from each other (with ratings, reviews, and queues not carrying over between them), and would have required separate user accounts. Also, the two websites would require separate subscriptions.[159][160][161][162]

On October 10, 2011, Netflix announced that it had shelved the planned re-branding in response to customer feedback and after the stock price plummeted nearly 30%, and that the DVD-by-mail and streaming services would continue to operate through a single website under the Netflix brand. Netflix stated that it had lost 800,000 subscribers in the fourth quarter of 2011—a loss partially credited to the poor reception of the aborted re-branding.[161][162][163]

In March 2012, Netflix confirmed to TechCrunch that it had acquired the domain name DVD.com. By 2016, Netflix had quietly rebranded its DVD-by-mail service under the name DVD.com, A Netflix Company.[164][165][166]

As of 2017, the service still had 3.3 million customers, and Hastings stated plans to keep it for at least five more years.[167] In the first quarter of 2018, DVD rentals earned $60.2 million in profit from $120.4 million in revenue.[168]

As of 2020, the DVD rental service is branded as DVD Netflix.[citation needed]

Profiles

In June 2008, Netflix announced plans to eliminate its online subscriber profile feature.[169] Profiles allow one subscriber account to contain multiple users (for example, a couple, two roommates, or parent and child) with separate DVD queues, ratings, recommendations, friend lists, reviews, and intra-site communications for each. Netflix contended that eliminating profiles would improve the customer experience.[170] However, likely as a result of negative reviews and reaction by Netflix users,[171][172][173] Netflix reversed its decision to remove profiles 11 days after the announcement.[174] In announcing the reinstatement of profiles, Netflix defended its original decision, stating, "Because of an ongoing desire to make our website easier to use, we believed taking a feature away that is only used by a very small minority would help us improve the site for everyone," then explained its reversal: "Listening to our members, we realized that users of this feature often describe it as an essential part of their Netflix experience. Simplicity is only one virtue and it can certainly be outweighed by a utility."[175]

Reintroduction

Netflix reinvigorated the "Profiles" feature on August 1, 2013, that permits accounts to accommodate up to five user profiles, associated either with individuals or thematic occasions. "Profiles" effectively divides the interest of each user, so that each will receive individualized suggestions and adding favorites individually. "This is important", according to Todd Yellin, Netflix's Vice President of Product Innovation, because, "About 75 percent to 80 percent of what people watch on Netflix comes from what Netflix recommends, not from what people search for".[176] Moreover, Mike McGuire, a VP at Gartner, said: "profiles will give Netflix even more detailed information about its subscribers and their viewing habits, allowing the company to make better decisions about what movies and TV shows to offer".[176] Additionally, profiles lets users link their individual Facebook accounts, and thus share individual watch queues and recommendations,[176][177] since its addition in March after lobbying Congress to change an outdated act.[177] Neil Hunt, Netflix's former Chief Product Officer, told CNNMoney: "profiles are another way to stand out in the crowded streaming-video space", and, "The company said focus-group testing showed that profiles generate more viewing and more engagement".[177]

Hunt says Netflix may link profiles to specific devices, in time, so a subscriber can skip the step of launching a specific profile each time they log into Netflix on a given device.[178]

Critics of the feature have noted:

- New profiles are created as "blank slates",[178] but viewing history prior to profile creations stays profile-wide.[179]

- People don't always watch Netflix alone, and media watched with viewing partner(s) – whose tastes might not reflect the owner(s) – affect recommendations made to that profile.[177][178][179]

In response to both concerns, however, users can refine future recommendations for a given profile by rating the shows watched and by their ongoing viewing habits.[178][179]

Subsidiaries

- DVD.com – Rents DVDs by mail

- Millarworld – A comic book company that was founded in 2004 by Scottish comic book writer Mark Millar as a creator-owned line.

- Netflix Pte. Ltd. – Netflix's studio in Singapore.

- Netflix Services UK Limited – A British division that holds Private limited with Share Capital.

- Netflix Streaming Services International B.V. – A Netflix subsidiary in the Netherlands.

- Netflix Streaming Services, Inc. – A subsidiary that licenses Netflix's content library for streaming.

- Netflix Global, LLC – A Foreign Limited-Liability Company filed on August 3, 2016, that co-produces all foreign programming and films

- Netflix Studios – A film and television studio that co-produces any original or foreign content.[180]

- Netflix Services Germany GmbH – A studio that contributes to German film subsidies supporting the domestic movie and TV production in the country.

- NetflixCS, Inc. – Another located 1108 E SOUTH UNION AVE Midvale, UT 84047.

- Netflix Luxembourg S.a r.l. – A subsidiary located in Luxembourg, Europe.

- Netflix Services Korea Ltd.- A subsidiary located in Seoul, South Korea.

- Netflix Entertainment Korea Ltd. - A contents subsidiary located in Seoul, South Korea.

Products

In 2007, Netflix recruited one of the early DVR business pioneers Anthony Wood to build a "Netflix Player" that would allow streaming content to be played directly on a television set rather than a PC or laptop.[181] While the player was initially developed at Netflix, Reed Hastings eventually shut down the project to help encourage other hardware manufacturers to include built-in Netflix support.[182] Wood eventually launched the player as the first device from Roku Inc. which is now primarily known for its streaming video players, with Netflix serving as a primary investor in the new company.[183]

In 2011, Netflix introduced a Netflix button for certain remote controls, allowing users to instantly access Netflix on compatible devices.[184]

Netflix revealed a prototype of the new device called "The Switch" at the 2015 World Maker Faire New York. "The Switch" allows Netflix users to turn off lights when connected to a smart home light system. It also connects to users' local networks to enable their servers to order takeout, and silence one's phone at the press of a button. Though the device hasn't been patented, Netflix released instructions on their website, on how to build it at home (DIY). The instructions cover both the electrical structure and the programming processes.[185][186]

Since 2015, the company received significant technical support from France's CNRS concerning video compression and formating, through CNRS' Laboratoire des Sciences du Numérique de Nantes (LS2N). In March 2017 at Barcelona's World Congress for mobile technologies, the American company presented the French lab's open-source technological creation: a compression tool allowing HD+ video quality with a bandwidth need of under 100 kilobytes per second, 40 times less than that of HDTV needs and compatible with mobile services worldwide.[187]

In May 2016, Netflix created a new tool called FAST to determine the speed of an Internet connection.[188] It received praise for being "simple" and "easy to use", and does not include advertisements, unlike other competitors.[189][190][191]

Content

Original programming

A "Netflix Original" is content that is produced, co-produced, or distributed by Netflix exclusively on their services. Netflix funds their original shows differently than other TV networks when they sign a project, providing the money upfront and immediately ordering two seasons of most series.[23]

In March 2011, Netflix began acquiring original content for its library, beginning with the hour-long political drama House of Cards, which debuted in February 2013. The series was produced by David Fincher, and starred Kevin Spacey.[192] In late 2011, Netflix picked up two eight-episode seasons of Lilyhammer and a fourth season of the ex-Fox sitcom Arrested Development.[193][194] Netflix released the supernatural drama series Hemlock Grove in early 2013.[195]

In February 2013, DreamWorks Animation and Netflix co-produced Turbo Fast, based on the movie Turbo, which premiered in July.[196][197] Netflix has since become a major distributor of animated family and kid shows.

Orange Is the New Black debuted on the streaming service in July 2013.[198] In a rare discussion of a Netflix show's ratings, Netflix executives have commented that the show is Netflix's most-watched original series.[199][200] In February 2016, Orange Is the New Black was renewed for a fifth, sixth and seventh season. On June 9, 2017, season 5 was premiered and the sixth season premiered on July 27, 2018.[201]

In November 2013, Netflix and Marvel Television announced a five-season deal to produce live-action Marvel superhero-focused series: Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Iron Fist and Luke Cage. The deal involves the release of four 13-episode seasons that culminate in a mini-series called The Defenders. Daredevil and Jessica Jones premiered in 2015.[202][203][204] The Luke Cage series premiered on September 30, 2016, followed by Iron Fist on March 17, 2017, and The Defenders on August 18, 2017.[205][206] In April 2016, the Netflix series in the Marvel Cinematic Universe were expanded further, to include a 13-episode series of The Punisher.[207][208] In addition to the Marvel deal, Disney announced that the television series Star Wars: The Clone Wars would release its sixth and final season on Netflix, as well as all five prior and the feature film. The new Star Wars content was released on Netflix's streaming service on March 7, 2014.[209]

In 2014, Netflix announced a four-movie deal with Adam Sandler and his Happy Madison Productions.[210] In January 2020, Netflix announced a new four-movie deal worth up to $275 million.[211]

In April 2014, Netflix signed Arrested Development creator Mitch Hurwitz and his production firm The Hurwitz Company to a multi-year deal to create original projects for the service.[212] The period drama Marco Polo premiered on December 12, 2014. The animated sitcom BoJack Horseman premiered in August 2014, to mixed reviews on release but garnering wide critical acclaim for the following seasons.[213]

The science fiction drama Sense8 debuted in June 2015, which was written and produced by The Wachowskis and J. Michael Straczynski.[214] Bloodline and Narcos were two other drama series that Netflix released in 2015. On November 6, 2015, Master of None premiered, starring Aziz Ansari. Other comedy shows premiering in 2015 included Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, Grace and Frankie, Wet Hot American Summer: First Day of Camp, and W/ Bob & David.

Netflix continued to dramatically expand their original content in 2016. The science fiction horror Stranger Things premiered in July 2016, music-driven drama The Get Down in August, British historical drama The Crown in November, and the year's premieres included comedy shows such as Love, Flaked, Netflix Presents: The Characters, The Ranch, and Lady Dynamite. Netflix released an estimated 126 original series or films in 2016, more than any other network or cable channel.[23] Some other Netflix originals are "Bird Box," staring Sandra Bullock in 2018 and "I Care a Lot," staring Rosamund Pike in 2020.

On September 14, 2016, Netflix and 20th Century Fox jointly acquired the US distribution rights to the Canadian independent drama film Two Lovers and a Bear following its screening at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 9, 2016.[215]

Netflix has also invested in distributing exclusive stand-up comedy specials from such notable comedians as Dave Chappelle, Louis C.K., Chris Rock, Jim Gaffigan, Bill Burr and Jerry Seinfeld.[216] In January 2017, Netflix announced all Seinfeld's Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee episodes and season 10 would be on their service.[217]

The company has started internally self-producing its original content, such as The Ranch and Chelsea, through its Netflix Studios production house.[218] Netflix expected to release 1,000 hours of original content in 2017.[219]

On August 7, 2017, Netflix acquired Millarworld, the creator-owned publishing company of comic book writer Mark Millar. It is the first ever company acquisition in Netflix's history. Netflix plans to leverage Millar and his current and future work for future original content. Chief content officer Ted Sarandos described Millar as being a "modern-day Stan Lee".[220] The following week, Netflix announced that it had entered into an exclusive development deal with Shonda Rhimes and her production company Shondaland.[221]

In October 2017, Netflix iterated a goal of having half of its library consist of original content by 2019, announcing a plan to invest $8 billion on original content in 2018. There will be a particular focus on films and anime through this investment, with a plan to produce 80 original films and 30 anime series.[222] In September 2017, Minister of Heritage Mélanie Joly also announced that Netflix had agreed to make a CDN$500 million (US$400 million) investment over the next five years in producing content in Canada. The company denied that the deal was intended to result in a tax break.[223][224] A study found that Netflix had realized this goal by December 2018.[225]

In November 2017, Netflix announced that it would be making its first original Colombian series, to be executive produced by Ciro Guerra.[226] The same month, Netflix announced it has signed an exclusive multi-year deal with Orange Is the New Black creator Jenji Kohan.[227] The following month, they signed Stranger Things director-producer Shawn Levy and his production company 21 Laps Entertainment to what sources say is a four-year, seven-figure deal.[228]

In May 2018, chief content officer Ted Sarandos stated that Netflix had increased its spending on original content, with 85% of its new content spending that year being devoted to it.[229] The company also announced a partnership with ESPN Films on a docuseries chronicling the 1997–98 Chicago Bulls season titled The Last Dance. It was released internationally on Netflix and became available for streaming in the United States three months after a broadcast airing on ESPN.[230][231]

On May 22, 2018, former president Barack Obama and his wife Michelle Obama signed a deal to produce docu-series, documentaries and features for Netflix under the Obamas' newly formed production company, Higher Ground Productions. On the deal, Michelle said "I have always believed in the power of storytelling to inspire us, to make us think differently about the world around us, and to help us open our minds and hearts to others."[232][233] Higher Ground's first film, American Factory, won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 2020.[234]

On August 16, 2018, Netflix announced a three-year overall deal with black-ish creator Kenya Barris. Under the deal, Barris will produce new series exclusively at Netflix, writing and executive producing all projects through his production company, Khalabo Ink Society.[235]

On August 27, 2018, Netflix signed a five-year exclusive overall deal with international best–selling author Harlan Coben. Under the multi-million pact, Netflix will work with Coben to develop 14 existing titles and future projects.[236] On the same day, the company inked an overall deal with Gravity Falls creator Alex Hirsch.[237]

In November 2018, Paramount Pictures signed a multi-picture film deal with Netflix as part of Viacom's growth strategy, making Paramount the first major film studio to sign a deal with Netflix.[238] A sequel to Awesomeness Films' To All the Boys I've Loved Before was released on Netflix under the title To All the Boys: P.S. I Still Love You as part of the agreement.[239]

On December 31, 2018, a concert film of Taylor Swift's Reputation Stadium Tour was released on Netflix.[240]

In January 2019, Sex Education made its debut as a Netflix original series with much critical acclaim. It was praised for its refreshing take on the teen dramedy genre with honesty, vulnerability, and raunch.[241]

In February 2019, it was announced that The Haunting creator Mike Flanagan had joined frequent collaborator Trevor Macy as a partner in Intrepid Pictures, and that the duo had signed an exclusive overall deal with Netflix to produce television content.[242]

On May 9, 2019, Netflix made a deal with Dark Horse Entertainment to make television series and films based on comics from Dark Horse Comics.[243] That same day, Netflix acquired the StoryBots children's media franchise as part of a commitment to expand its educational content.[244][245]

In early August 2019, Netflix negotiated an exclusive multi-year film and television deal with Game of Thrones creators/showrunners David Benioff and D.B. Weiss reportedly worth US$200 million.[246][247] As a result of their commitments to Netflix, Benioff and Weiss withdrew from an earlier agreement with Disney to write and produce a Star Wars film series.[248][249][250] The first Netflix production created by Benioff and Weiss will be an adaptation of Liu Cixin's science fiction novel The Three-Body Problem and the rest of the Remembrance of Earth's Past trilogy[clarification needed].[citation needed]

On September 30, 2019, in addition to renewing Stranger Things for a fourth season, Netflix announced they had signed the series’ creators The Duffer Brothers to a nine-figure deal for additional films and televisions shows over multiple years.[251]

On November 13, 2019, Netflix and Nickelodeon entered into a multi-year content production agreement to produce several original animated feature films and television series based on Nickelodeon's library of characters, in order to compete with Disney's new streaming service Disney+, which had launched the day before. This agreement expanded on their existing relationship, in which new specials based on the past Nickelodeon series Invader Zim and Rocko's Modern Life (Invader Zim: Enter the Florpus and Rocko's Modern Life: Static Cling respectively) were released by Netflix. Glitch Techs was the first series to be released as part of the new agreement. Other new projects planned under the team-up include a music project featuring Squidward Tentacles from the animated television series SpongeBob SquarePants, and films based on The Loud House and Rise of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.[252][253][254] In early March 2020, ViacomCBS announced that it will be producing two spin-off films based on SpongeBob SquarePants for Netflix.[255]

In January 2020, Gwyneth Paltrow's series The Goop Lab was added as a Netflix Original. This led to widespread criticism of the streaming company for giving Paltrow a platform to promote her company Goop, which has been criticized for making unsubstantiated claims about the effectiveness of the health treatments and products it promotes.[256][257][258][259] That same month, Gloria Sanchez Productions entered a multi-year non-exclusive first-look television deal with Netflix, and also entered a feature multi-year deal with Paramount Pictures.[260]

On February 25, 2020, Netflix formed partnerships with six Japanese creators to produce an original Japanese anime project. This partnership includes manga creator group CLAMP, mangaka Shin Kibayashi, mangaka Yasuo Ohtagaki, novelist and film director Otsuichi, novelist Tow Ubutaka, and manga creator Mari Yamazaki.[261]

On April 7, 2020, Peter Chernin and his company Chernin Entertainment made a multi-year first-look deal with Netflix to make films.[262]

In September 2020, it was announced that Netflix signed a multi-million dollar deal with the Duke and Duchess of Sussex. Harry and Meghan agreed to a multi-year deal promising to create TV shows, films, and children's content as part of their commitment to stepping away from the duties of the royal family.[263][264]

In December 2020, Netflix offered Millie Bobby Brown a huge first look deal to develop and star in a number of projects for them including a potential action franchise.[265]

Film and television deals

Netflix currently has exclusive pay TV deals with several studios. The pay TV deals give Netflix exclusive streaming rights while adhering to the structures of traditional pay TV terms. Netflix's United States library includes newer releases from Relativity Media and its subsidiary Rogue Pictures,[266] as well as DreamWorks Animation[267] (until May 2018, when the studio signed a new contract with Hulu),[268] Open Road Films[269] (though this deal expired in 2017; Showtime has assumed pay television rights[270]), Universal Animation (for animated films declined by HBO), FilmDistrict,[271] The Weinstein Company (whose co-founder, Harvey Weinstein, has been accused of sexual harassment as of 2017 (see Harvey Weinstein sexual abuse allegations), causing Netflix to withdraw from hosting the 75th Golden Globe Awards with TWC, and ending its Golden Globes partnership with the mini-major film studio[272]),[273][274] Sony Pictures Animation,[275] and the Walt Disney Studios (until 2019) catalog.

Other distributors who have licensed content to Netflix include Warner Bros., Universal Pictures, Sony Pictures Entertainment and The Walt Disney Studios (including 20th Century Fox). Netflix also holds current and back-catalog rights to television programs distributed by Walt Disney Television, DreamWorks Classics, Kino International, Warner Bros. Television and CBS Television Distribution, along with titles from other companies such as Allspark (formerly Hasbro Studios), Saban Brands, Funimation, and Viz Media.[276] Formerly, the streaming service also held rights to select television programs distributed by NBCUniversal Television Distribution, Sony Pictures Television and 20th Century Fox Television. Netflix also previously held the rights to select titles from vintage re-distributor The Criterion Collection, but these titles were pulled from Netflix and added to Hulu's library.[277] One of the more significant acquisitions was for the show Breaking Bad, produced by Sony Pictures Television. Netflix acquired the rights after the show's third season in 2010, at a point where original broadcaster AMC had expressed the possibility of cancelling the show. Sony pushed Netflix to release Breaking Bad in time for the fourth season, which as a result, greatly expanded the show's audience on AMC due to new viewers binging on the Netflix past episodes, and doubling the viewership by the time of the fifth season. Breaking Bad is considered the first such show to have this "Netflix effect".[278]

Epix signed a five-year streaming deal with Netflix. For the initial two years of this agreement, first-run and back-catalog content from Epix was exclusive to Netflix. Epix films would come to Netflix 90 days after their premiere on Epix. However, the exclusivity clause ended on September 4, 2012, when Amazon signed a deal with Epix to distribute its titles via the Amazon Video streaming service.[279] These include films from Paramount, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Lionsgate.[280][281]

On September 1, 2011, Starz ceased talks with Netflix to renew their streaming arrangement. As a result, Starz's library of films and series were removed from Netflix on February 28, 2012. Titles available on DVD were not affected and can still be acquired from Netflix via their DVD-by-mail service.[282] However, select films broadcast on Starz continue to be available on Netflix under license from their respective television distributors.

Netflix also negotiated to distribute animated films from Universal that HBO declined to acquire, such as The Lorax, ParaNorman, and Minions.[283]

On August 23, 2012, Netflix and The Weinstein Company signed a multi-year output deal for RADiUS-TWC films.[284] Later that year, on December 4, Netflix and Disney announced an exclusive multi-year agreement for first-run United States subscription television rights to Walt Disney Studios' animated and live-action films, which were available on Netflix beginning in 2016. However, classics such as Dumbo, Alice in Wonderland and Pocahontas were instantly available upon completion of the deal.[285] Direct-to-video releases were made available in 2013.[286][287] The agreement with Disney ended in 2019, as the company was preparing to launch a new streaming service that would carry all Walt Disney Pictures, Marvel Studios, and Lucasfilm releases. Netflix retains the rights to continue streaming the Marvel series that were produced for the service.[288] With the Disney-Fox merger, movie and TV titles from 20th Century Fox will likely follow suit after their deal with Netflix expires,[289] except Two Lovers and a Bear and The Woman in the Window which Netflix will likely retain US streaming rights to as Fox and Netflix jointly acquired the US distribution rights to Two Lovers and a Bear, and Netflix acquired distribution rights to The Woman in the Window from 20th Century Studios.[215][290]

Time Warner CEO Jeff Bewkes in 2011 welcomed Netflix's ability to monetize older content that was previously not generating money for media companies.[291] On January 14, 2013, Netflix signed an agreement with Time Warner's Turner Broadcasting System and Warner Bros. Television to distribute Cartoon Network, Warner Bros. Animation, and Adult Swim content, as well as TNT's Dallas, beginning in March 2013. The rights to these programs, previously held by Amazon Video, were given to Netflix shortly after their deal with Viacom to stream Nickelodeon and Nick Jr. programs expired.[292] However, Cartoon Network's ratings dropped by 10% in households that had Netflix, and so many of the shows from that channel and Adult Swim were removed in March 2015.[293] Most of these shows were added to Hulu in May of the same year.[294]

In Canada, Netflix holds pay TV rights to films from Paramount, DreamWorks Animation and 20th Century Fox (shared with The Movie Network[295]), distributing all new content from those studios eight months after initial release. In 2015, the company also bought the Canadian pay TV rights to Disney films.[296]

In 2014, opinion blogger Felix Salmon wrote that Netflix could not "afford the content that its subscribers most want to watch".[297] He cited as evidence the company's loss of rights to stream several major movies. According to journalist Megan McArdle, the loss of these movies was extremely problematic for the company; specifically, she said that "[Netflix's] movie library is no longer actually a good substitute for a good movie rental place".[298]

Netflix also began to acquire distribution rights to third-party films in 2017 into 2018. One of its first acquisitions was the film The Cloverfield Paradox, which Netflix had acquired from Paramount Pictures in early 2018, and launched on its service on February 4, 2018, shortly after airing its first trailer during Super Bowl LII. While the film was critically panned, analysts believed that Netflix's purchase of the film helped to make the film instantly profitable for Paramount compared to a more traditional theatrical release, while Netflix benefited from the surprise reveal.[299][300] Other films acquired by Netflix include international distribution for Paramount's Annihilation[300] and Universal's News of the World and worldwide distribution of Universal's Extinction,[301] Warner Bros.' Mowgli: Legend of the Jungle[302] and Paramount's The Lovebirds. In February 2020, after Mattel Television ended the deal to broadcast the British television series Thomas & Friends on Nickelodeon in the US, they made a deal to stream the show in March 2020, making it the first time in years that Thomas content was available on Netflix. As of March 2020, Netflix offered just under 3,000 film titles for streaming on its US service.[303] This does not include multi-episode titles (series). On August 3, 2020, it was announced Netflix was in final talks to acquire the distribution rights to the film The Woman in the Window from 20th Century Studios.[290]

Producers and distributors

The following only applies to the United States. Listed companies may still or may not have licensing agreements with Netflix in other territories.

Current

- 9 Story Media Group

- Aniplex of America

- Bleecker Street

- Boat Rocker Media

- Chernin Entertainment

- Entertainment One

- ErosSTX

- Fox Entertainment

- Funimation

- Gaumont Film Company

- Hasbro

- Kino International

- Lionsgate

- Mattel

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

- Nelvana

- NBCUniversal

- Open Road Films

- Red Chillies Entertainment

- Relativity Media

- Saban Brands

- Scholastic

- Shout! Factory

- Skydance Media

- Studio 100

- Sony Pictures

- TBS

- The Pokémon Company

- ViacomCBS

- Viz Media[276]

- WarnerMedia

- WildBrain

- Wow Unlimited Media

- Xilam

Former

Interactive content

Netflix has released some content that is interactive on certain devices,[305][306] allowing the user to make choices that change the story and accompanying video track:

| Title | Type | Released |

|---|---|---|

| Black Mirror: Bandersnatch | Film[307] | December 28, 2018 |

| The Boss Baby: Get That Baby! | Animation[308] | September 1, 2020 |

| Buddy Thunderstruck: The Maybe Pile | Animation[309] | July 14, 2017 |

| Captain Underpants Epic Choice-o-Rama | Animation[310] | February 11, 2020[311] |

| Carmen Sandiego: To Steal or Not to Steal | Animation[312] | March 10, 2020[313] |

| Minecraft: Story Mode | Animation[314] | November 27, 2018 |

| Puss in Boots: Trapped in an Epic Tale | Animation[315] | June 20, 2017 |

| Spirit Riding Free: Ride Along Adventure | Animal Tales[316] | December 8, 2020 |

| Stretch Armstrong: The Breakout | Animation[317] | March 13, 2018 |

| Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt: Kimmy vs. the Reverend | Sitcom[318] | May 12, 2020[319] |

| You vs. Wild | Series[320] | April 10, 2019 |

In June 2018, Netflix announced a partnership with Telltale Games to port its adventure games to the service in a streaming video format. The games would be adapted to be similar to the existing interactive narrative stories that Netflix already offers, allowing simple controls through a television remote. The first such game, Minecraft: Story Mode, was expected to be released later in the year, and Telltale also received rights to produce a video game adaptation of Stranger Things for conventional gaming platforms.[321][322] In September 2018, Telltale underwent a "majority studio closure" and laid off nearly its entire staff beyond a skeleton crew of 25 employees, citing a loss of funding. Netflix stated that while the Minecraft: Story Mode port would go on, the company was seeking alternate options for the Stranger Things project.[323][324][325]

Device support and technical details

Netflix can be accessed via an internet browser on PCs, while Netflix apps are available on various platforms, including Blu-ray Disc players, tablet computers, mobile phones, smart TVs, digital media players, and video game consoles (including Xbox One, PlayStation 4, Wii U, Xbox 360, and the PlayStation 3). The Wii and the PlayStation 2 were formerly compatible with Netflix as well.

In addition, a growing number of multichannel television providers, including cable television and IPTV services, have also added Netflix apps accessible within their own set-top boxes, sometimes with the ability for its content (along with those of other online video services) to be presented within a unified search interface alongside linear television programming as an "all-in-one" solution.[326][327][328][329]

4K streaming requires a 4K-compatible device and display, both supporting HDCP 2.2. 4K streaming on personal computers requires hardware and software support of the Microsoft PlayReady 3.0 digital rights management solution, which requires a compatible CPU, graphics card, and software environment. Currently, this feature is limited to 7th generation Intel Core or later CPUs, Windows 10, Nvidia GeForce 10 series and AMD Radeon 400 series or later graphics cards, and running through Microsoft Edge web browser, or the Netflix universal app available on Microsoft Store.[330][331][332][333][334]

Sales and marketing

During Q1 2011, sales and rentals of DVDs and Blu-rays plunged about 35%, and the sell-through of packaged discs fell 19.99% to $2.07 billion, with more money spent on subscription than in-store rentals. This decrease was attributed to the rising popularity of Netflix and other streaming services.[335]

In July 2012, Netflix hired Kelly Bennett – former Warner Bros. Vice President of Interactive, Worldwide Marketing – to become its new chief marketing officer. This also filled a vacancy at Netflix that had been empty for over six months when their previous CMO Leslie Kilgore left in January 2012.[336]

Netflix's website had 117.6 million subscribers as of 2018, with 8.3 million being added in the fourth quarter of 2017.[337]

Netflix has a Twitter feed, used to tweet about the new and upcoming shows that include hashtags to encourage engagement of their audience to not only watch the show but to contribute to the hashtag themselves.[338]

International expansion

| 2007 | Netflix began streaming in the United States. |

|---|---|

| 2010 | The company first began offering streaming service to the international market on September 22, 2010, in Canada.[339] |

| 2011 | Netflix expanded its streaming service to Latin America, the Caribbean, Belize and the Guianas.[340] |

| 2012 | Netflix started its expansion to Europe in 2012, launching in the United Kingdom and Ireland on January 4.[341] By October 18 it had expanded to Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden.[342] |

| 2013 | The company decided to slow expansion to control subscription costs.[343] It only expanded to the Netherlands. |

| 2014 | Netflix became available in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, and Switzerland.[344] |

| 2015 | Netflix expanded to Australia and New Zealand, Japan,[345][346][347] Italy, Portugal, and Spain.[348] |

| 2016 | Netflix announced at the Consumer Electronics Show in January 2016 that it had become available worldwide except China, Syria, North Korea and the territory of Crimea.[349][350] |

| 2017 | In April 2017, Netflix confirmed it had reached a licensing deal in China for original Netflix content with IQiyi, a Chinese video streaming platform owned by Baidu.[351] |

As of October 2020[update], Netflix officially supports 30 languages for user interface and customer support purposes: Arabic (Modern Standard), Chinese (Simplified and Traditional), Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Hindi, Hungarian, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Malay, Norwegian (Bokmål), Polish, Portuguese (Brazilian and European), Romanian, Russian, Spanish (Castilian and Latin American), Swahili, Swedish, Thai, Turkish and Vietnamese.[352][353][354]

Netflix has encountered political controversy after its global expansion and for some of its international productions, including The Mechanism, Fauda and Amo.[355][356] In June 2016, Russian Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky asserted that Netflix is part of a US government plot to influence the world culture, "to enter every home, get into every television, and through that television, into the head of every person on earth". This was part of his argument for the increase of funding of Russian cinema to pitch it against the dominance of Hollywood.[357]

In February 2020, the company released its first report of when it has complied with government requested content takedowns in their countries, a total of 9 times since its launch:[358][359][360]

- In Singapore, Netflix complied with requests to take down Cooking on High, The Legend of 420, and Disjointed in 2018, The Last Temptation of Christ in 2019, and The Last Hangover in 2020.

- In Germany, Netflix complied with a request to take down the 1990 remake of Night of the Living Dead in 2017.[361]

- In Vietnam, Netflix complied with a request to take down Full Metal Jacket in 2017.

- In New Zealand, Netflix complied with a request to take down the film The Bridge in 2015. The film is deemed objectionable by the country's Office of Film and Literature Classification.[362]

- In Saudi Arabia, Netflix complied with a request to take down an episode criticizing the country's government from the series Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj in 2019, which drew criticism in the media.[363][364]

In India, Netflix along with Disney's Hotstar announced plans in early 2019 to adopt self-regulation guidelines for content streamed on their platforms within the country in an effort to prevent potential implementation of government censorship laws.[365] The Jordanian series Jinn was condemned by members of the country's government for contravening the country's moral standards, and the country's highest prosecutor has sought to have the series banned from streaming.[366] On September 3, 2019, Netflix applied for a license to continue its streaming services in Turkey, under the country's new broadcasting rules. The television watchdog of Istanbul, Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK) issued new guidelines, under which content providers were required to get new license for operating in the country.[367] Netflix was later ordered by the RTÜK to remove LGBT characters from their Turkish original series Love 101 and The Protector.[368][369] Netflix subsequently cancelled the ongoing production of its Turkish series If Only which was also being ordered to remove a gay character to be allowed release.[370]

Worldwide users

| End of year | paying VOD customers (in millions) | paying DVD customers (in millions) |

|---|---|---|

| Q4 2013[371] | 41.43 | 6.77 |

| Q4 2014[371] | 54.48 | 5.67 |

| Q4 2015[372] | 70.84 | 4.79 |

| Q4 2016[372] | 89.09 | 4.03 |

| Q4 2017[373] | 110.64 | 3.33 |

| Q4 2018[373] | 139.26 | 2.71 |

| Q4 2019[374] | 167.09 | 2.21 |

| Q1 2020[121] | 182.86 | N/A |

| Q2 2020[121] | 192.95 | N/A |

| Q4 2020[375] | 203.66 | N/A |

Competitors

Netflix's success was followed by the establishment of numerous other DVD rental companies, both in the United States and abroad. Walmart began an online rental service in October 2002 but left the market in May 2005. However, Walmart later acquired the rental service Vudu in 2010.[376]

Blockbuster Video entered the United States online market in August 2004, with a US$19.95 monthly subscription service (equivalent to $30,91 in 2022). This sparked a price war; Netflix had raised its popular three-disc plan from US$19.95 to US$21.99 just prior to Blockbuster's launch, but by October, Netflix reduced this fee to US$17.99. Blockbuster responded with rates as low as US$14.99 for a time, but, by August 2005, both companies settled at identical rates.[377] On July 22, 2007, Netflix dropped the prices of its two most popular plans by US$1.00 in an effort to better compete with Blockbuster's online-only offerings.[378] On October 4, 2012, Dish Network scrapped plans to make Blockbuster into a competitor for Netflix's online service.[379] (Dish bought the ailing Blockbuster, LLC in 2011, and at that point planned to maintain franchise locations as well as its "Blockbuster on Demand" streaming service. By 2020, Blockbuster on Demand had been discontinued, and only one Blockbuster franchise location remains in Oregon.)[380][381]

In 2005, Netflix cited Amazon.com as a potential competitor,[382] which until 2008, offered online video rentals in the United Kingdom and Germany. This arm of the business was eventually sold to LoveFilm; however, Amazon then bought LoveFilm in 2011.[383] In addition, Amazon now streams movies and television shows through Amazon Video (formerly Amazon Video On Demand and LOVEFiLM Instant).[384]

Redbox is another competitor that uses a kiosk approach: Rather than mailing DVDs, customers pick up and return DVDs at self-service kiosks located in metropolitan areas. In September 2012, Coinstar, the owners of Redbox, announced plans to partner with Verizon to launch Redbox Instant by Verizon by late 2012.[385] In early 2013, Redbox Instant by Verizon began a limited beta release of its service,[386] which was described by critics as "No Netflix killer"[387] due to "glitches [and] lackluster selection".[388]

CuriosityStream, a premium ad-free, subscription-based service launched in March 2015 similar to Netflix but offering strictly nonfiction content in the areas of science, technology, civilization and the human spirit, has been dubbed the "new Netflix for non-fiction".[389]

Hulu Plus, like Netflix and Amazon Prime Instant Video, "ink[s] their own deals for exclusive and original content", requiring Netflix "not only to continue to attract new subscribers, but also keep existing ones happy".[390]

Netflix largely avoids offering pornography, but several "adult video" subscription services were inspired by Netflix.[391][392]

In Australia, Netflix most notably competes with Stan, the local SVOD competitor that only operates in the Australian marketplace and currently undercuts Netflix on monthly pricing while using extensive original Australian content as its major value proposition. Netflix currently holds a sizeable lead in market share over Stan, with Netflix reaching over 11.5 million household users in Australia in 2019 compared to Stan reaching over 2.5 million household users in the same period.[393][394] In the Nordic countries, Netflix competes with Viaplay, HBO Nordic and C More.[395][396] In Southeast Asia, Netflix competes with iflix,[397] Astro On the Go, iWant TFC, Sky on Demand, Singtel TV, and HomeCable OnDemand.[398] In New Zealand, Netflix competes with local streaming companies including Television New Zealand (TVNZ),[399] Mediaworks New Zealand, Sky Network Television,[400] Lightbox,[401] Neon and Quickflix.[402] In Italy, Netflix competes with Infinity, Now TV and TIMvision.[403] In South Africa, Netflix competes with Showmax.[404] In the MENA region, Netflix competes with icflix, Starz Play Arabia, OSN's Wavo, and iflix Arabia. Also, in Brazil, Netflix competes with Globoplay, a Grupo Globo's streaming service.

In Mexico, Televisa removed its content from Netflix in 2016 and moved it to its own streaming service Blim.[405]

The Walt Disney Company launched their own streaming service, Disney+, in November 2019. As a result, most Disney content that had been available on Netflix was removed.[406][407] Disney reported in early 2020 that their subscriber count had blown past internal and industry estimates at 50 million globally - a 22 million increase since the prior report two months earlier.[408]

Awards

On July 18, 2013, Netflix earned the first Primetime Emmy Award nominations for original online-only web television programs at the 65th Primetime Emmy Awards. Three of its web series, Arrested Development, Hemlock Grove and House of Cards, earned a combined 14 nominations (nine for House of Cards, three for Arrested Development and two for Hemlock Grove).[409] The House of Cards episode "Chapter 1" received four nominations for both the 65th Primetime Emmy Awards and 65th Primetime Creative Arts Emmy Awards, becoming the first webisode of a television series to receive a major Primetime Emmy Award nomination: David Fincher was nominated in the category of Outstanding Directing for a Drama Series.[409][410] "Chapter 1" joined Arrested Development's "Flight of the Phoenix" and Hemlock Grove's "Children of the Night" as the first webisodes to earn Creative Arts Emmy Award nomination, and with its win for Outstanding Cinematography for a Single-Camera Series, "Chapter 1" became the first webisode to be awarded an Emmy.[411] Fincher's win for Directing for a Drama Series made the episode the first Primetime Emmy-awarded webisode.[412]

On December 12, 2013, the network earned six Golden Globe Award nominations, including four for House of Cards.[413] Among those nominations was Wright for Golden Globe Award for Best Actress – Television Series Drama for her portrayal of Claire Underwood, which she won at the 71st Golden Globe Awards on January 12. With the accolade, Wright became the first actress to win a Golden Globe for an online-only web television series. It also marked Netflix' first major acting award.[414][415][416] House of Cards and Orange is the New Black also won Peabody Awards in 2013.[417]

On July 10, 2014, Netflix received 31 Emmy nominations. Among other nominations, House of Cards received nominations for Outstanding Drama Series, Outstanding Directing in a Drama Series and Outstanding Writing in a Drama Series. Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright were nominated for Outstanding Lead Actor and Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series. Orange is the New Black was nominated in the comedy categories, earning nominations for Outstanding Comedy Series, Outstanding Writing for a Comedy Series and Outstanding Directing for a Comedy Series. Taylor Schilling, Kate Mulgrew, and Uzo Aduba were respectively nominated for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series, Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Comedy Series and Outstanding Guest Actress in a Comedy Series (the latter was for Aduba's recurring role in season one, as she was promoted to series regular for the show's second season).[418]